Lyme disease is caused by a kind of bacteria called Borrelia. Most of the time, the bacteria lives in ticks and mice (or other animals in the wild) and doesn’t bother anybody. The ticks feed on blood from animals, attaching to bigger animals as they grow themselves.

Ecology and life cycle

Lyme disease and ticks

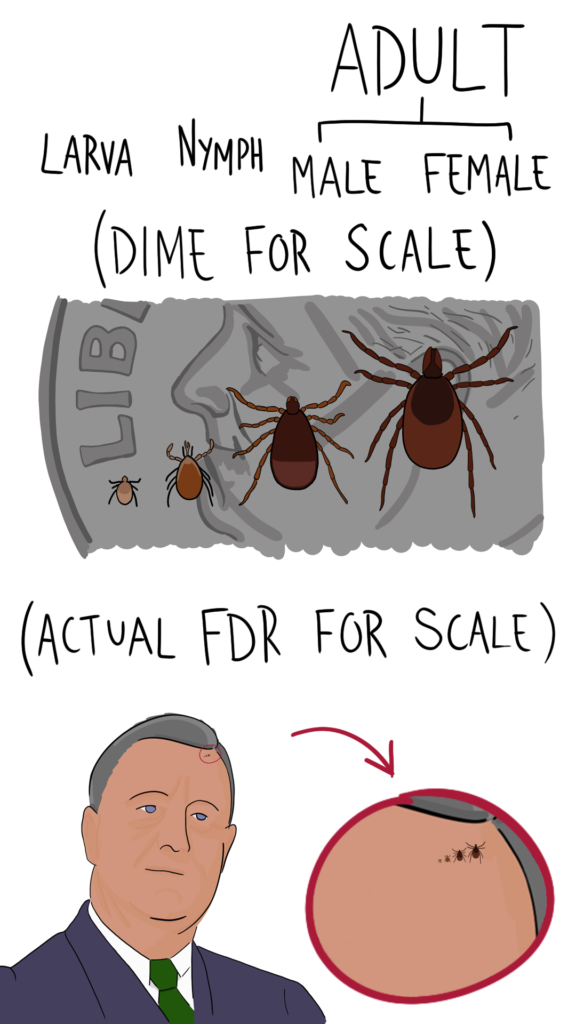

The newly-hatched ticks, called larvae, are about the size of a poppy seed and feed on mice or small birds. After they’ve had a tasty meal of mouse blood, they fall off and grow a little bigger over winter. In spring they reappear as nymphs, which aren’t as cute or magical as the name makes them seem. Being a little bigger (maybe the size of a sesame seed) they can feed on bigger animals like foxes, deer, or people. Again, they grow after their meal and become fully-grown adults, which are about the size of a lentil but more difficult to cook with. Male and female adults look slightly different, but only if you look really close.

They get around twice as big after each meal. If that continued, it would take eight or nine meals before the tick got to be the size of a cat. Luckily that isn’t how it works and they stop growing once they become adults.

The adults give birth to eggs, which hatch in springtime and the cycle starts all over again. Fortunately for us, the larva don’t hatch infected with Borrelia – they usually pick it up from an infected animal when they feed for the first time. Ticks can pick up the infection from any infected animal at any stage of their life cycle. Once they are infected they stay infected for the rest of their lives, because there aren’t any tick doctors to cure them. Infected ticks will pass the bacteria on to any animal they feed on, not just humans – this is how the bacteria persist in the environment.

The fact that the tick is essential for the transmission of Lyme disease gives us a lot of unusual ways to prevent the disease. Stopping ticks from biting people is the obvious way – we do this by wearing insect repellent and covering up when we’re outside. If we managed to clear the infection from the wild mice, then the tick larvae would never pick the bacteria up and then it wouldn’t matter even if they did feed on humans. We can also try to control the numbers of ticks in the wild. We can do this by spraying insecticides, or by managing the populations of animals like deer which are breeding grounds for ticks.

One study in Finland found that when they released wolves into a national park, the deer population went down because the wolves ate some deer. This caused tick numbers to go down, and therefore so did rates of Lyme disease. It’s possible that we could reduce Lyme disease by releasing loads and loads of wolves across America, but admittedly that might cause other problems. Personally I still think it’s worth a shot.